This is a topic that comes up once every while, but has wide-reaching implications for many parts of the UnrealScript language and mod development,

particularly when working on the Highlander. We’re going to delve into the internals of property storage and, more practically, clear up why you can’t

pass booleans as out parameters, and why attempts to add variables to native classes have been

unceremoniously shot down.

What even are properties

Intuitively, properties is the term UnrealScript uses for variables, though this definition leaves room for interpretation as to what a variable exactly is.

Consider the following code snippet:

class MyClass extends Object;

var int GlobalCounters[2]; // int property of arity 2 in class

struct SomeStruct

{

var bool Cached; // bool property in struct

var bool PrevValue; // bool property in struct

var array<int> ChangeCounters; // int array property in struct

};

var SomeStruct State; // struct property in class

delegate OnConditionChange(bool NewValue); // delegate property in class

// Argument properties vvvvvvvvvvvvvvv--vvvvvvvv

function bool CheckCondition(Actor ChkObject, int Fact, out string Dbg) {

// ^^^^ bool property return out property ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

local float Tmp; // float property in function

// complicated logic omitted

return Tmp > 0.0f;

}

I’ve marked all properties with comments. The code snippet demonstrates that there are different kinds of properties, corresponding to the UnrealScript types:

- Primitive types like Byte/Enum, Int, Bool, Float, Name

- Composite types like Struct, Map

- Owning types like Array, String

- Reference types like Object, Interface, Delegate

We can make a reverse observation: All properties have an owner! This code snippet exhibits the three kinds of property owners UnrealScript has:

- Classes

- Structs

- Functions

Finally, the astute reader has noticed the var int GlobalCounters[2] – all properties have

an arbitrary, but fixed at compile-time arity – properties can store a fixed number of values (by default 1).

Where’s the data?

Naïve implementation

In a very simplistic implementation, the properties would own the data themselves. There would be a Property class:

class Property extends Field abstract;

var name PropertyName;

var int Arity;

All different property kinds would be implemented in a fairly similar manner1:

class FloatProperty extends Property;

var float Value[Arity];

Note that these examples use a syntax similar to UnrealScript. The actual implementation would, of course, be written in C++.

Our property owner would then look something like this:

class Class extends Object;

var Class SuperClass;

var array<Property> Properties;

Instantiating a class is then simply a matter of cloning the Properties array of the class and all its super classes and their contents.

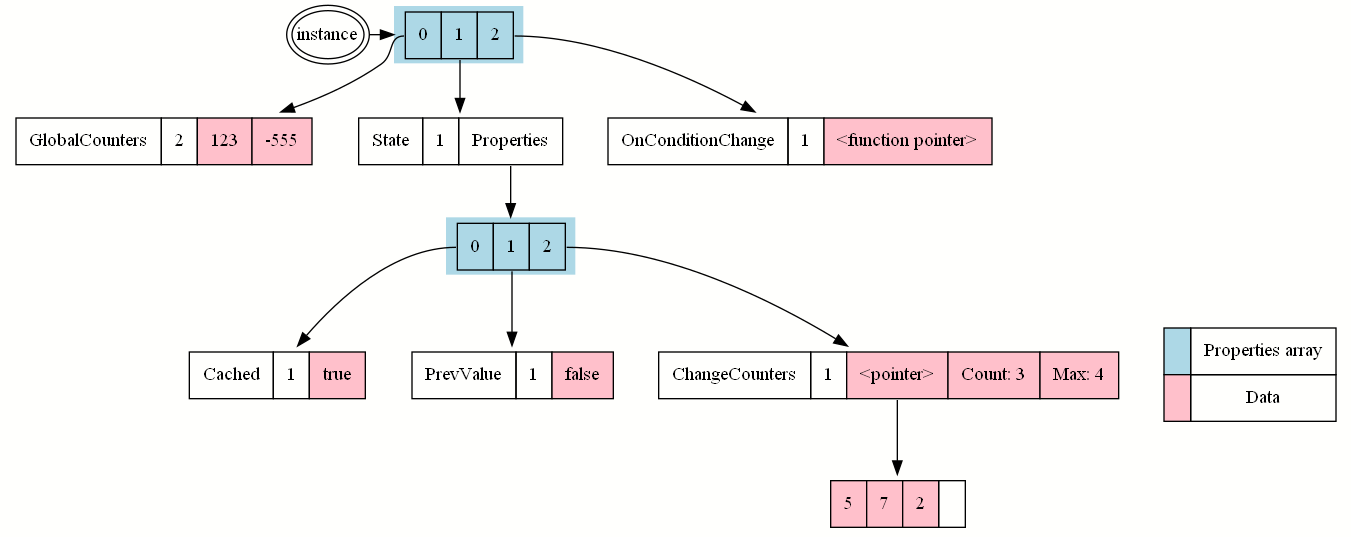

Let’s visualize how this naïve implementation stores the class property data:

There are several problems with this approach:

- It wastes space!

- Even without an actual instance, our properties store some value even though it’s not useful.

- Instances store copies of metadata like name, arity even though it stays constant for all instances.

- It wastes performance!

- Every property is a new allocated object, so getting to the property data requires following at least two pointers, which is bad for CPU cache efficiency:

- The

Propertiesarray must allocate its contents somewhere because the number of properties isn’t known, and even different for different classes. Getting to the array contents is the first pointer indirection. - Every

Propertiesentry itself is a reference to an object allocated somewhere, so we have to follow another pointer.

- The

- Instantiating a class requires copying all metadata.

- Every property is a new allocated object, so getting to the property data requires following at least two pointers, which is bad for CPU cache efficiency:

- It’s inconvenient to efficiently work with on the C++ (native) side! C++ has a fairly predictable layout algorithm and places all member data (class/struct variables) into one contiguous memory region, with one allocation for the entire class or struct. It would be great to lay out all data in the exact same way so that we get C++ interoperability for free.

Borrowing from C++

This last point offers a very practical solution: We store the property data in one big chunk of bytes, and instead of having our properties store the data themselves, they instead store where in that data chunk the property data lies:

class Property extends Field abstract;

var name PropertyName;

var int Arity;

var int Offset;

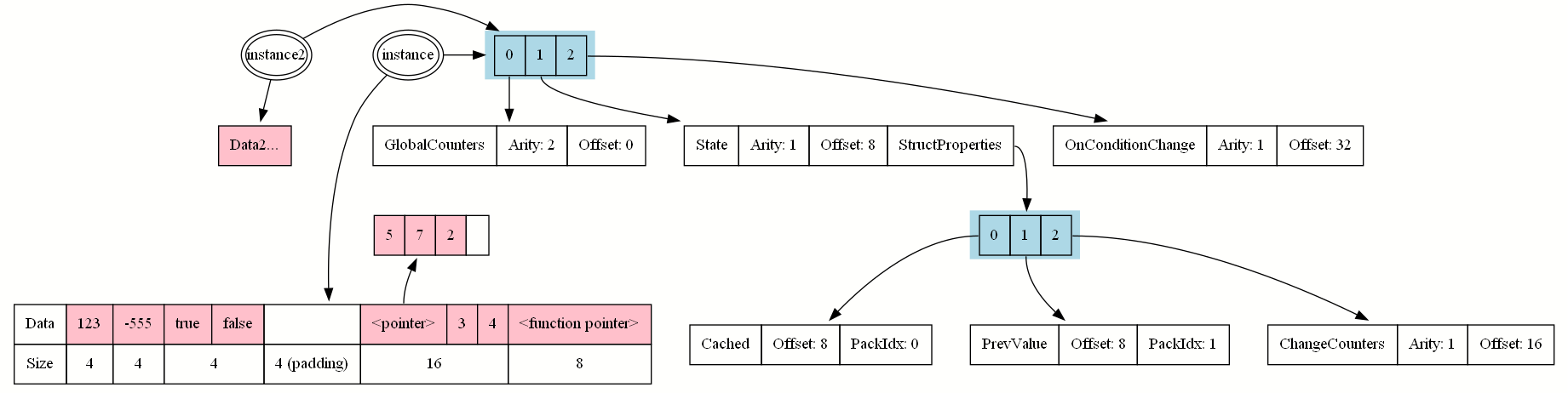

This is a massive improvement: Even if we instantiate our class hundreds of times, all instances share the same property metadata and only the pink-colored data is unique to instances. Every property has an offset that matches the position of the data in the data block.

The array data isn’t stored in that same block because we don’t know in advance how many elements will be stored, and accordingly the array

allocates storage separately.

If we were to mark our class and struct as native, the compiler would automatically generate the following header file:2

struct FSomeStruct

{

BITFIELD Cached:1;

BITFIELD PrevValue:1;

TArray<INT> ChangeCounters;

};

class UMyClass : public UObject

{

public:

//## BEGIN PROPS MyClass

INT GlobalCounters[2];

struct FSomeStruct State;

FScriptDelegate __OnConditionChange__Delegate;

//## END PROPS MyClass

}

For UnrealScript, the exact layout doesn’t really matter: When a script package is loaded, the UnrealScript code within references the properties by name, and the dynamic linker will translate those names into offsets once, at load time.

For C++ however, this data layout is important: As long as the UnrealScript compiler lays out the property data the exact same way as

the C++ compiler used for the game, the data pointer ObjectInstance->Data pointing to a seemingly random chunk of bytes can be re-interpreted

as a pointer to a UMyClass *; a pointer to a C++ class.

“The way data is laid out in memory” is part of the ABI, the Application Binary Interface. Even though C++ doesn’t guarantee any particular layout, the UnrealScript compiler just needs to match what the particular C++ compiler does.

Most notably, C++ places alignment requirements on some data: A 64-bit pointer needs to be placed at addresses that are a multiple of 8 bytes,

so we have some padding to round up from 12 to 16 bytes between the booleans and the ChangeCounters array.

The C++ side has no dynamic linker for properties. Changes to native class or struct properties cause a change in the header file and require a full re-compile of the C++ side.

If the C++ side is not recompiled, native will access variables at the wrong offsets and will read and write garbage data.

Do not modify the properties of native classes or structs. Modders have no way to re-compile any C++ code, so ABI-incompatible changes cause unfixable problems. The compiler and game will sometimes even error out at startup time for some changes.

Native-only types

The C++ header has a TArray<INT> corresponding to an array<int>. These two types have the exact same data layout,

so both UnrealScript code and C++ code can use the same array with the same data without any conversion costs. This array

type is built into the engine combined with appropriate UnrealScript op-codes to access this array.

But there are also types that cannot be accessed from UnrealScript, but are important to have in a class for native code. Consider the UnitValues map:3

var private native Map_Mirror UnitValues{TMap<FName, FUnitValue>};

This corresponds to the following C++ declaration:

class UXComGameState_Unit : public UXComGameState_BaseObject, public IX2GameRulesetVisibilityInterface, public IX2VisualizedInterface, public IDamageable

{

public:

//## BEGIN PROPS XComGameState_Unit

// ...

TMap<FName, FUnitValue> UnitValues;

C++ has no problems accessing this map, but there are no ways to access the map from UnrealScript. What is Map_Mirror even defined as?

struct pointer

{

var native const int Dummy;

};

struct BitArray_Mirror

{

var native const pointer IndirectData;

var native const int InlineData[4];

var native const int NumBits;

var native const int MaxBits;

};

struct SparseArray_Mirror

{

var native const array<int> Elements;

var native const BitArray_Mirror AllocationFlags;

var native const int FirstFreeIndex;

var native const int NumFreeIndices;

};

struct Set_Mirror

{

var native const SparseArray_Mirror Elements;

var native const int InlineHash;

var native const pointer Hash;

var native const int HashSize;

};

struct Map_Mirror

{

var native const Set_Mirror Pairs;

};

Wow! That’s a lot! All of this is necessary to exactly mirror the C++ data layout. All properties are const to prevent UnrealScript from

mucking with native data structures, while C++ code can freely work with this map. Notably, these structs are kept in sync manually:

The {TMap<FName, FUnitValue>} suffix in the declaration tells the UnrealScript compiler to simply generate a declaration with an entirely

different native type instead of using Map_Mirror.

Booleans

If we review the Borrowing from C++ section, there’s a few weird things about booleans:

- Several booleans have the same offset

- Booleans have an extra

PackIndex - C++ implements them with

BITFIELD <name>:1

It turns out that UnrealScript stores up to 32 consecutive booleans as individual bits of a 32-bit integer. In order to address a boolean, we not only need the address of that integer, but also the individual bit index.

As a consequence, the UnrealScript virtual machine has separate op-codes for boolean property assignment and other property assignment.

There’s also an op-code for out property assignment, but not one for out boolean property assignment.

out bool is thus unsupported.

Functions

We’ve mentioned before how not only classes and structs, but also functions can own properties. Let’s re-visit our example function:

function bool CheckCondition(Actor ChkObject, int Fact, out string Dbg) {

local float Tmp;

// complicated logic omitted

return Tmp > 0.0f;

}

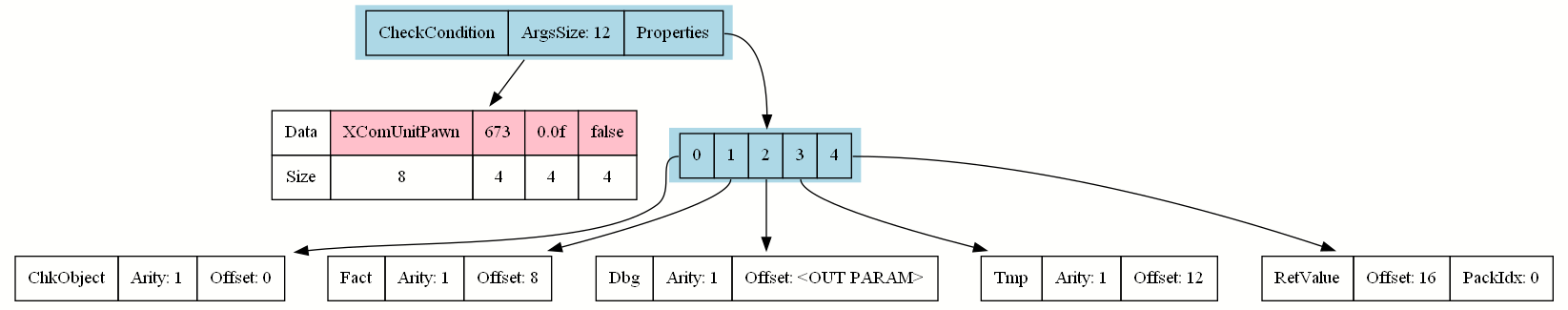

It turns out that functions do something extremely similar to classes. All function arguments and local properties are allocated in one chunk:

Both function arguments and local properties are part of the stack frame – a data block allocated for all these properties upon calling the function. The out parameter is not present in this data block because out parameters live somewhere else – the entire point of out parameters is to skip the part where the data needs to be copied to the stack frame and back; and the code directly writes to the borrowed storage location.

There’s even a hidden return property that the function writes to upon returning; the UnrealScript VM retrieves the return value from there.

There is a difference between class properties and function argument properties: Class properties are accessed by name, but when we call a function we pass the function arguments by index. If we switched around arguments in package A, package B that calls this function needs to not only be re-compiled, but also re-written since the argument order and types no longer match.

One exception are optional parameters; they may be added to the end of the arguments list without breaking dependent UnrealScript code.

As always, native code makes things more complicated. For example, the following event

static event ModifyTacticalTransferStartState(XComGameState TransferStartState)

{

}

is turned into the following call stub:

struct X2DownloadableContentInfo_eventModifyTacticalTransferStartState_Parms

{

class UXComGameState* TransferStartState;

};

class UX2DownloadableContentInfo : public UObject

{

public:

// ...

void eventModifyTacticalTransferStartState(class UXComGameState* TransferStartState)

{

X2DownloadableContentInfo_eventModifyTacticalTransferStartState_Parms Parms(EC_EventParm);

Parms.TransferStartState=TransferStartState;

ProcessEvent(FindFunctionChecked(XCOMGAME_ModifyTacticalTransferStartState),&Parms);

}

}

Similarly, we can’t modify the arguments list of existing events: This C++ code allocates the data block for all function arguments

on the stack as a X2DownloadableContentInfo_eventModifyTacticalTransferStartState_Parms struct and copies the arguments into it

(similar to what a data block for class properties looks like), so the C++ side assumes a fixed size and offsets.

Strictly speaking, this doesn’t only apply to events. Events are more convenient to call from C++, but nothing prevents native code from calling regular functions the same way. Usually it’s safe to assume only events are called from C++.

One thing that works in our favor here is that functions are found by name (with FindFunctionChecked) when calling, so we can easily add

functions to native classes without breaking the ABI.

Closing Words

There’s a closely related topic we’ve approached in the last part of this post: Function dispatch. In a separate blog post, we’re going to look at how functions are called, out parameters are implemented, and how subtyping/variance interacts with them.