Welcome to Too Unreal, a blog post series about some lesser-known aspects of the XCOM 2 engine and the Unreal Engine 3 that it is based on, particularly about UnrealScript.

This series is not going to be a modding tutorial, but is instead meant to provide some additional details and insights into how things work under the hood. At the same time, I’m not keeping it too dry – this series will contain case studies, personal anecdotes, and advice that will be useful to keep in mind if you end up working on more sophisticated UnrealScript code.

Other topics I plan on covering are data layout, out parameters and subtyping, function dispatch, multitasking. I’m also open to suggestions; this blog uses utterances for comments.

In this blog post, we’re going to explore how strings and names in UnrealScript work.

Textbook definitions

The official UnrealScript documentation ends up being quite terse:

string

A string of characters.

name

The name of an item in Unreal (such as the name of a function, state, class, etc). Names are stored as an index into the global name table. Names correspond to simple strings of up to 64 characters. Names are not like strings in that they are immutable once created.

This intuitively matches what we expect from those data types:

local name MyName, MyName2;

local string MyString, MyString2;

MyString = "Hi";

MyString2 = MyString;

MyString $= ", ÜC!"; // mutate string

`log(MyString); // ScriptLog: Hi, ÃœC!

MyName = 'Adv';

MyName2 = MyName;

MyName $= 'M1'; //❌ Error, Left type is incompatible with '$='

MyName = 'Other'; // re-assignment isn't mutation

Let’s delve into a bit more detail about how these data types might be implemented under the hood.

Strings

UnrealScript hides a lot of the complexity here but the C++ side needs to allocate memory for every variable.

For a 32-bit integer (int), this size is known at compile-time (4 bytes), but a string can have arbitrary length (and grow/shrink at runtime).

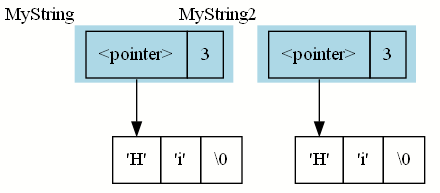

As a result, the string stores its data as a separate allocation:

With this, the data needed to store the string has a fixed size: A pointer to the actual data and the string length.

These strings are terminated with a NUL character, as is common in the C world.

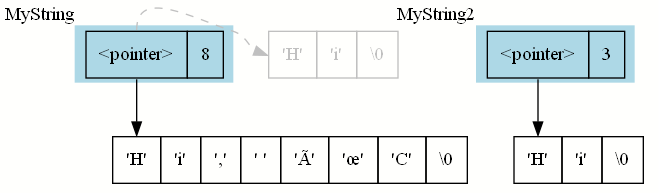

Let’s see what happens when we append the ", ÜC!" to the existing string:

The string re-allocates: It allocates a new, longer block of memory, copies the old data into it, appends the new string, and throws away (“frees”) the old data. That’s why we can freely mutate a string. But this means that creating a copy of the string requires a new allocation and duplicates the string data: If both strings pointed to the same data, changing one string would change the other too – or worse, we would throw away data that the other string is still referring to!

Encoding Woes

Unfortunately, the string isn’t what we expected: Instead of printing as “Hi, ÜC!”, it output “Hi, ÃœC!”. This is a consequence of the Unreal Engine 3 only supporting the ASCII and UTF-16 encodings when the original source file was saved in the UTF-8 encoding.

Encodings are the way we represent codepoints (“characters”) of the character set as bytes. The most common character set is Unicode, and UTF-16 is one possible encoding. UTF-16 uses two bytes per character; UTF-8 uses 1-4 bytes per character.

ASCII is a mostly alphanumeric subset of Unicode that only requires one byte per character, and all ASCII strings encode to the same bytes as the equivalent UTF-8 string.

The Unreal Engine recognizes UTF-16 files by a Byte-Order-Mark (BOM), two unprintable bytes at the beginning of a file that indicate an UTF-16 encoding. An UTF-8 file has no BOM, so the compiler (being part of the engine) believes that the file is ASCII only and interprets the two bytes needed to represent the “Ü” codepoint as two ASCII characters “Ô and “œ”.

Restrict yourself to ASCII-only code. Localize strings, and save localization files with an UTF-16 BOM encoding.

Some software, particularly source code management tools like git, will interpret UTF-16 files as binary files and not text. It can be useful

to store localization files in UTF-8 and convert to UTF-16 as part of the build process, as done by Long War of the Chosen in its custom build script.

Names

Even though the official documentation makes it seem like names are reserved for built-in things, we can use names for anything! Case in point, the XCOM 2 engine uses names for Templates and configuration array entries like loot, loadouts or encounters.

Names have some unique properties not mentioned in the documentation:

- The empty name,

'', compares equal to the name'None'. - Name comparison is case-insensitive:

'MyName' == 'mYnAmE'.

Let’s look a bit into how this global name table works.

The Name Table

The documentation says that names are stored as an index into the name table. This means that instead of owning the string data, a name is basically just a fancy int. We have a number of requirements for the implementation:

- Names should reliably and efficiently be comparable: Two names should compare equal if and only if their indices are equal. This means that comparing two names is as efficient as comparing two

ints. - Names should be efficiently created: No matter how many thousand names we already have, creating a name from a string should always take the same, low amount of time.

- Names should efficiently be serialized: While storing names as integers is great when the game is running, we should save them as strings when we write them to a file so that we don’t have to rely on the numbers being the same when the game boots up the next time (spoiler: they wouldn’t be).

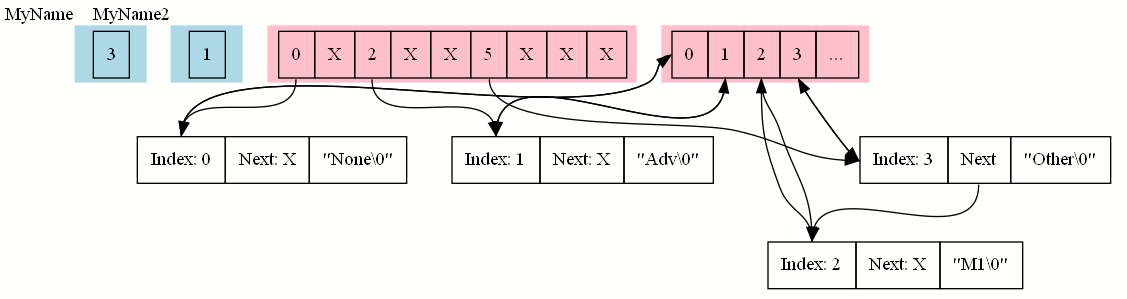

There are two pieces needed to make this work: The first is a name array; an ever-growing array containing every single name created, without duplicates. Whenever we want to create a name not already present in the name table, we can simply generate a new index by looking at the array length; and we can look up the string behind a name by indexing into this array. This piece already solves (1.) and (3.)!

When creating a name, we have to check if a that name already exists – otherwise, we could end up with the same name twice, and the same name would have a different index. Unfortunately, we’d have to iterate over the whole name array to find a name comparing equal. The Unreal Engine 3 solves this by employing a hash set.

This hash set is a fixed-size array with a comparatively low number of entries (say 32768), and we use a hash function to find the correct entry (“container”, “bucket”) for a given string. When we create a name from a string, we find the correct bucket, and check if the name is already there. If so, we have an existing name and re-use the index. If not, we add the new name to the name array and insert it also into this bucket.

The pigeonhole principle states that “if n items are put into m containers, with n > m, then at least one container must contain more than one item”.

Applied to our hash set, there will be collisions: Different names will have the same hash, otherwise we could never have more than 32768 names. This means that we store multiple names in the same bucket, and still have to check multiple existing names to see if any of them match (although I’m unsure about the exact implementation, we’re going to assume that the Unreal Engine 3 uses linked list chaining).

However, instead of checking N existing names, we only check N / 32768 names. Much better!

In addition to the special name 'None', we’ll consider the three names from our code snippet: 'Adv', 'M1', and 'Other'. Let’s see what our data structures look like:

In our example, the names were inserted in the afore-mentioned order. 'None' has the hash 0, 'Adv' the hash 2, and 'M1' and 'Other' both share the hash 5. When we created the name Other, M1 was already in that bucket, M1 does not compare equal to Other, so we linked 'Other' before 'M1' and placed 'Other' into that bucket.

Names are an Unreal Engine 3 implementation of string interning: For every string, we only store data once, and can then cheaply create and compare several instances of the string.

Memory leaks

This implementation never reclaims unused name data. Once we create a name, it will reside in the name table (and thus memory) until the game is closed! We can easily test this with the following code:

local string BaseString;

local name TempName;

local int i;

BaseString = "MySomewhatLongerBaseStringForHigherMemoryUsage";

`log("Starting...");

for (i = 0; i < 35000000; ++i)

{

TempName = name(BaseString $ "_" $ i);

if (i % 500000 == 0)

{

`log(i); // progress indicator and timer

}

}

`log("Done!");

Let’s estimate the memory usage:

"MySomewhatLongerBaseStringForHigherMemoryUsage" is 46 characters long. We add an underscore and 8 digits, and the NUL character (total 112 bytes with our above knowledge of strings). We require 4 bytes for the index, 8 bytes (on a 64-bit system) for the Next pointer, and another 8 bytes for the pointer entry in the names array. We expect memory usage to rise by about 112B * 35e6 = 4.62GB.

The measurements were performed on an Intel Core i5-3470 @ 3.20GHz, launched through a console command in TQL (to minimize interference from the game).

- Time: 39.86s

- Memory usage increase: 0MB

Wait, what? Our memory usage had no significant change!

Let’s revisit what our assumption would practically mean: When we new an object, say new class'XComLWTuple', the engine assigns a unique name to that object.

We start with XComLWTuple_0, then XComLWTuple_1 etc. Even though our XComLWTuples are garbage collected, we never re-use existing numbers: Our tuple object names are monotonically increasing.

If names worked that way, we would reliably end up polluting our name table; and even though UnrealScript has a garbage collector, we would end up leaking memory!

The Number Optimization

Simply put, a _Number suffix is stripped before interning. Our names don’t actually consist of one number, but two numbers instead. The first number is an index into the name array, the second number is the numeric suffix.

Let 'XComLWTuple' be our sixth name. Then the name 'XComLWTuple' would be represented as 6|0 (0 for no suffix). 'XComLWTuple_0' would be represented as 6|1, 'XComLWTuple_1' as 6|2, 'XComLWTuple_345' as 6|346.

Our example code managed to trigger this optimization: Our names are 'MySomewhatLongerBaseStringForHigherMemoryUsage_0', 'MySomewhatLongerBaseStringForHigherMemoryUsage_1', and so on. This means that the game interns the MySomewhatLongerBaseStringForHigherMemoryUsage once and all our synthetic names re-use that index, just with a different number part. Testing two names for equality is thus a matter of comparing the two integers of the two names.

Let’s Break It For Real

With this knowledge, we can try to circumvent this optimization:

local string BaseString;

local name TempName;

local int i;

BaseString = "MySomewhatLongerBaseStringForHigherMemoryUsage";

`log("Starting...");

for (i = 0; i < 35000000; ++i)

{

//TempName = name(BaseString $ "_" $ i);

TempName = name(i $ "_" $ BaseString);

if (i % 500000 == 0)

{

`log(i); // progress indicator and timer

}

}

`log("Done!");

- Time: 848.09s

- Memory usage increase: 3.11GB1

With this snippet, we leaked more than 3 Gigabytes of memory. This memory is permanently leaked and will not be reclaimed until we close the game.

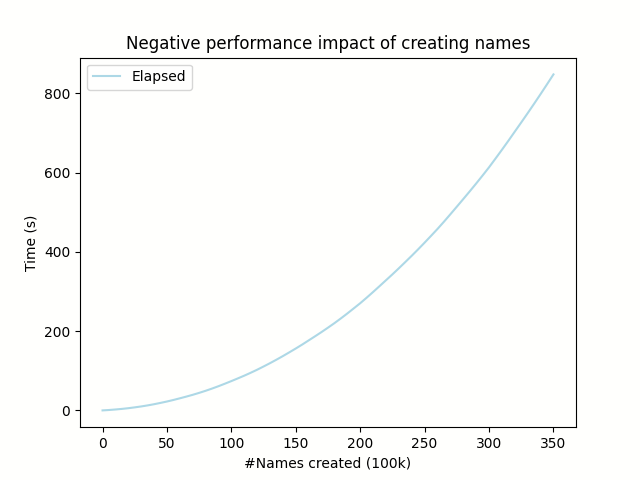

There is another problem: With every name we synthesize, our hash set becomes less efficient. We never resize the 32768 entries large hash set, so we have more and more collisions, and we have to check longer and longer lists of interned names whenever we create another name. We can plot the elapsed duration over the number of names created:

The trained programmer recognizes this as an O(n^2) algorithm; An algorithm whose runtime is quadratic to some input size. The more names we add, the longer it takes to add another name. Algorithms like this are best avoided.

Of course, 35 million names are a bit extreme, but not that extreme – crash dumps indicate that a normally running game has about three million interned strings.

But this explains why we cannot concatenate names, and have to go through strings: A name type that conveniently allows concatenation and mutation would make it extremely easy to accidentally pollute the name table and inhibit performance until we close the game.

Names are usually only created at game startup (including template creation code). Names should only contain alphanumeric characters and underscores.

Avoid synthesizing arbitrary names after that, only convert from string -> name when necessary. _Number suffixes, however, are free.

Capitalization

We’ve explored the string -> name conversion in detail, but there’s one pitfall when going from name -> string: We can’t rely on any particular capitalization:

local int MYcUstOMnAmE;

`log('MyCustomName'); // ScriptLog: MYcUstOMnAmE

The Unreal Engine uses names to represent the name of (among other things) local variables, so when the compiler encounters the 'MyCustomName' string, the name has already been interned as "MYcUstOMnAmE". The name -> string conversion uses the first representation of the name it encountered, and that’s MYcUstOMnAmE.

Flash UI

You can actually cause breakage with this if even if you personally never interact with any code that relies on capitalization! Here’s a super cursed hack you can try in the Highlander:

// in CHDLCInfoTopologicalOrderNode.uc

var bool LeftPanel;

And suddenly we broke our loadout menu:

This is because UIArmory_Loadout has this code:

EquippedListContainer = Spawn(class'UIPanel', self);

EquippedListContainer.bAnimateOnInit = false;

EquippedListContainer.InitPanel('leftPanel');

This creates a UIPanel that links up with a panel of the name leftPanel on the Flash side – except Flash is case-sensitive even though Firaxis’ API takes names! The compiler parses our LeftPanel first, and when it encounters the leftPanel, LeftPanel is the interned representation.

Never rely on the name -> string conversion to make any sense at all. Never display names to the user, only use them for debugging purposes.

If you interact with existing Flash UI directly, ensure you don’t have name conflicts with differing capitalization. In your own mods, you can’t break base game UI because you compile after base-game packages, but especially when working on the Highlander or when developing sophisticated UI, this is a huge footgun.

Warning, INI file contains an incorrect case for

There is a particularly annoying compiler warning that sporadically appears for some config variables:

//⚠️ Warning, INI file contains an incorrect case for (CoverType) should be (coverType)

var config ECoverType coverType;

This warning references an INI file even when we haven’t modified any config files at all! This warning should better be described with

Warning, config variable coverType actually named CoverType

because the compiler had, at some point (perhaps even in XComGame) seen the name CoverType, so this variable is actually called CoverType.

In fact, the compiler seemingly records this mismatch because config files are actually case-sensitive, and the runtime is clever enough to

not use an arbitrary string representation of the variable name when loading from config.

To “fix” it, either follow the opposite of the advice and call it CoverType, or choose an entirely different name.

Closing Words

That’s it for the first entry in the series! If there is anything you’d like to have clarified regarding this topic, feel free to reach out in the comments!

Similarly, I’m open to suggestions for topics to cover next.

This memory usage is lower than expected. This is because names representable in ASCII are stored as ASCII to save space. The same happens when saving strings to packages or save files. ↩︎