It’s common wisdom that “the Unreal Engine 3 is single-threaded”. Despite that, there are some less and some more surprising sources of parallelism that can happen in UnrealScript, particularly XCOM 2.

In this post, we’ll first look at how one frame in the Unreal Engine 3 works (in particular, actor and component ticking) and the kind of parallelism happening there, and then move over to some more sources of concurrency and parallelism.

What happens in a frame

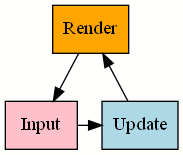

Before we can talk about what happens in parallel, we need to establish what actually happens in a single frame. On a very high level, most games have a game loop that looks something like Input->Gameplay->Render:

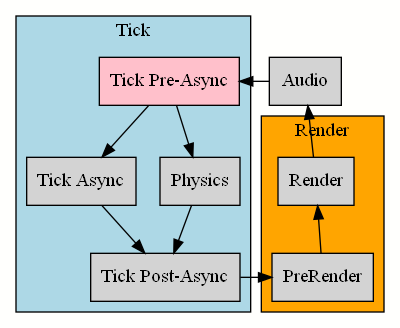

The Unreal Engine 3 documentation offers bullet points about its internal workings,1 here’s that information in form of a graph:

It turns out there are actually three different ticks in the engine – one tick running before physics, one tick running together with

physics, one tick after physics. Every actor ticks in one of these groups unless the game is paused; input is usually handled before physics.

All these ticks receive an argument DeltaTime, passing the passed world time in seconds since the last tick.

This world time is not real time! The engine can run in slow-motion or fast-forward by scaling this DeltaTime down or up,

try the console command slomo 2 for faster tactical gameplay.

Pause is not slomo 0! In pause, most actors don’t tick at all. slomo has a minimum scale of x0.1.

Physics

Not only the input, almost all things tick before physics by default:2

defaultproperties

{

// For safety, make everything before the async work. Move actors to

// the during group one at a time to find bugs.

TickGroup=TG_PreAsyncWork

}

It makes sense to run most gameplay ticks before physics to give physics an opportunity to immediately react to changes from gameplay.

At the same time, some things must run after physics, for example camera positioning. If the camera positioned itself before physics and physics then moved the object the camera was focusing on, the camera would lag behind by one entire frame (up to 30ms at 30 FPS).

And then, there’s code that can run safely in parallel with physics without any issues. This is a performance optimization: On any machine with more than one CPU core, running more things in parallel with physics is “free” as long as physics are more expensive.

This is helped by the fact that the actual physics update runs no UnrealScript code at all, so the engine doesn’t immediately explode when

it runs UnrealScript code together with physics. On the other hand, UnrealScript code running TG_DuringAsyncWork should not access any variables

touched by physics, which would cause unpredictable behavior in face of incomplete results.

Very few things actually use TG_DuringAsyncWork, mostly because it’d be surprising and premature optimization is the root of all evil.

All code that doesn’t run in parallel with physics blocks the entire game loop. For example, if the AI decides to move a unit (somewhere in the Pre-Async Tick), it needs to select an appropriate tile – from a list of potentially hundreds of tiles! This scoring of tiles takes quite a bit of time and for the entire duration of that loop, nothing in the game can make progress. The longer this takes, the more noticeable the arising short lag spike.

Games are real-time programs. Depending on the desired frame rate, there is a soft deadline of 33ms (30 FPS), 17ms (60 FPS), or 7ms (144 FPS). When the total computations for a single frame take longer than that, we miss the deadline. This doesn’t cause any problems with the hardware, but it degrades the quality of the service.

Cooperative Multitasking

Splitting Work

The UnrealScript implementation of tile scoring manages about 30 tiles per millisecond on my Intel Core i5-3470 @ 3.20GHz. However, several hundred target tiles aren’t unusual: Even the earliest units in the game (with a comparatively low mobility) have about 60 target tiles in a wide single-level Gatecrasher map. Terror missions with high-mobility units, several building floors and complex cover situations can make this a whole lot more expensive.

On the other hand, tile scoring isn’t urgent. It’s totally fine to only score a few tiles in one frame, a few in the next frame, and so on until it’s done:

function StartScoringTiles()

{

TilesToScore = //... retrieve tiles list from native cache

IsScoringTiles = true;

}

event Tick(float DeltaTime)

{

super.Tick(DeltaTime);

if (IsScoringTiles)

{

// Score 50 tiles...

}

if (TilesToScore.Length == 0)

{

IsScoringTiles = false;

}

}

There is no parallelism going on. Every frame, we spend most of our time on “the usual”, and a little bit of time on tile scoring. At the same time, we clearly kick off the tile scoring task and it’s done at some later point without blocking on its completion.

This illustrates the difference between concurrency and parallelism. Parallelism happens when two tasks make progress at the same time, concurrency allows tasks to start and complete in overlapping time periods even though only one task can make progress at a time.

This can only work because the AI system is built with the ability to wait for results in the first place, and wouldn’t work if it immediately demanded results. We call this cooperative multi-tasking because our code needs to explicitly stop doing its work for other code to resume.

Timers

This works great, but has the small problem that our Tick function becomes a bit overcrowded. We have to remember to call

super.Tick(DeltaTime), and for every task we could ever run, our Tick function becomes lengthier. We can fix this by using native timers:

function StartScoringTiles()

{

TilesToScore = //... retrieve tiles list from native cache

IsScoringTiles = true;

SetTimer(0.001f, false, nameof(ScoreTiles)); // Set non-repeating timer in 1ms

}

function ScoreTiles()

{

// Score 50 tiles...

if (TilesToScore.Length > 0)

{

SetTimer(0.001f, false, nameof(ScoreTiles)); // Queue another 50 tiles

}

else

{

IsScoringTiles = false;

}

}

This keeps our Tick function tidy and our deadlines happy.

Async loading

This is basically what the game does when asynchronously loading objects in the background. Every frame, the Unreal Engine 3 dedicates at most 5 milliseconds to background loading.

This makes our loading performance (as well as our earlier AI calculations) dependent on the frame rate. We can calculate the loading efficiency (percentage of time spent on loading; performing a blocking load would be 100%):

| Regular frame rate | Async-loading frame rate | Loading Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| 30 FPS | 26.1 FPS | 13% |

| 60 FPS | 46.2 FPS | 23% |

| 144 FPS | 83.7 FPS | 42% |

| → ∞ FPS | 200 FPS | 100% |

XCOM 2 (vanilla) uses async loading for the entire tactical map while viewing the dropship. On a machine that manages about 30 FPS in the dropship (no matter whether CPU or GPU performance is to blame), the tactical map takes more than seven times as long to load than would be necessary.

War of the Chosen shows a black screen while loading the map, which brings us close to the optimal performance and speeds up the tactical transition by a factor of 7 on low-end machines!

State code

In the example we’ve looked at before, we had a task that is computationally expensive but easy to split up. It turns out that there is also the opposite kind of task: A task that is complex enough to not be trivially breakable, but spends a lot of time just waiting.

One such example is the code that sets up the tactical session. We have to wait for the UI to be ready, then do a bit of setup, then wait for the dropship to be ready, wait for the plot to load in, wait for the map to generate, wait for the map pieces to load in, wait for the mission intro to finish, and then we can start the actual battle:3

state CreateTacticalGame

{

Begin:

while (UIBusy())

{

Sleep(0.0f);

}

StartLoadingDropship();

while (DropshipLoading())

{

Sleep(0.0f);

}

ShowDropship();

StartLoadingMap();

while (MapLoading())

{

Sleep(0.0f);

}

HideDropship();

BuildMapData();

SpawnUnits();

while (MissionIntroPlaying())

{

Sleep(0.0f);

}

GotoState('TurnPhase_Begin');

}

State code is allowed in Actors and automatically executed when the actor ticks.

Sleep is a latent function: When we call it, the UnrealScript virtual machine saves that the Actor was in that particular state and called that

function, returns from state code execution, and checks again next frame.

A Sleep(0.0f) immediately resumes execution the next frame – upon which our loops just check the condition again and go to

sleep if not met. Implemented with functions and timers, this would be spread across over 10 functions.

Latent functions are actually return statements in disguise: They return upon calling them and continue execution at some point in the future.

State code is also often used with Actions and the animation system – Pawns have a latent FinishAnim function that plays an animation

and resumes execution when the animation has played. Here is a simplified copy of the Grapple action:

state Executing

{

Begin:

UnitPawn.StartAnim('NO_GrappleFire');

while( ProjectileHit == false )

{

Sleep(0.0f);

}

// Have an emphasis on seeing the grapple tight

Sleep(0.1f);

UnitPawn.StartAnim('NO_GrappleStart');

while( !ReachedTarget() )

{

if( !UnitPawn.PlayingAnim() )

{

break;

}

Sleep(0.0f);

}

// send messages to do the window break visualization

SendWindowBreakNotifies();

FinishAnim(UnitPawn.PlayAnim('NO_GrappleStop'));

CompleteAction();

}

The XComIdleAnimationStateMachine, also making use of state code, has a function TurnTowardsPosition4

that only resumes execution in that state when the animation system has driven the pawn to turn towards a position. This can take

several seconds in world time.

Remember how I said latent functions are return statements in disguise? There’s not really a way to save something in locals for us to use after we call return, so state code can’t have local variables. Code between latent function calls can be factored out into regular functions with locals, but state saved across latent function calls must be saved in class variables.

Other programming languages like C++, C#, Python, Rust and many more call this programming paradigm stackless coroutines.

Relevant keywords are async, await, generator, yield.

Most programming languages automatically derive the state saved across yield points (which latent function calls are) and save them in an anonymous object. UnrealScript is rather simplistic, that’s why locals in state code aren’t allowed.

Preemptive Multitasking

Sometimes cooperative multitasking isn’t a viable solution – either because we can’t rely on other code cooperating with important code, or because the task itself doesn’t have predictable yield points.

Audio

The Audio mentioned in the game loop diagram is Unreal Engine 3’s audio (SoundCues) and notably does not run in parallel with anything.

If a frame takes a bit too long, the audio backend runs out of audio data to… convert into sound5 and the audio starts stuttering.

This is because the audio system does a little bit of work every frame (to fill the audio buffers), but it can’t defend against other tasks taking too long when it’s part of the game loop.

XCOM 2 solves this problem by using a custom audio middleware called Wwise, which runs on an entirely different operating system thread and only exchanges simple events and messages with the game loop. This allows it to make sound without waiting for audio data by running in parallel with the game code.

The operating system has a scheduler that regularly switches between the threads that a process has spawned (or runs several of them in parallel) and ensures that all threads – including the main thread and the audio thread – can do their work. Pausing a thread this way, without cooperation, is called preemption; switching to another thread requires a context switch.

The operating system is pretty powerful. It will save the call stack and CPU registers so that the thread can resume the next time from the exact point it was preempted. The same mechanism also allows multiple processes to run on one machine – every process has at least one thread.

Physics also makes use of that functionality, with a small difference: Audio uses a thread that always runs for the entire runtime of the game, while the physics task is joined so that the main thread continues with Post-Async Tick only after physics are done.

Even though mod developers have no convenient way to author Wwise audio, music pieces should not be implemented with SoundCues because the stuttering is just awful.

If you’re interested in using Wwise for music, nintendoeats adapted my Music Modding System to Wwise audio and wrote a guide for those wanting to make use of Wwise for music packs.

Game states

One of the most expensive kinds of calculations is building a new tactical game state, especially when it drags a long chain of events after it (consider a long movement triggering several reaction shots and environmental damage). We’ve explored in a previous blog post how all game states are immediately built upon confirming the action. In the vanilla game, this most often causes a short but noticeable freeze upon confirming an ability, and a reduced frame rate and stuttering if AI reacts and builds game states in the frames after.

We can’t really apply our previous solutions because cooperative multitasking requires our tasks to be able to easily yield control to the game loop at certain intervals. We just can’t do this with game states – context and state submission are a recursive and unpredictable algorithm. Often we trigger certain events and every listener might decide to do whatever.

War of the Chosen changes game state submission so that when we submit a context, we perform building the game state (and all its response states) on a separate OS thread. We don’t wait for it to be done, but once it’s done, we can use the results. The History is enhanced with some thread-local data6 to allow the game state thread to access the currently built states, while the main thread still looks at the tip of the latest fully built event chain.

I don’t believe Firaxis enhanced the UnrealScript virtual machine to the point where two OS threads can run UnrealScript in parallel – many data structures and globals are not thread-safe, and employing locks would be a huge performance degradation.

My best guess is that even though we have several OS threads, only one of them is running UnrealScript at a time while the other is just parked by the OS. The engine could then switch off the game state thread at certain safe points like the end of statements. That way we get the state-saving logic for free from the OS without really implementing any cooperation.

The game’s UI won’t allow you to perform any other actions while a game state is being built, but it fixes the visual freeze. It also subverts one of our fundamental assumptions: At any point in tactical, a game state might be in flight on another thread.

If you write code that allows the user to initiate context or game state submissions in tactical, you must check that

`XCOMGAME.GameRuleset.IsDoingLatentSubmission() returns false. Otherwise two threads will be building game states

in parallel – a race condition.

Closing Words

Turns out there’s quite a bit of nuance to concurrency and parallelism in UnrealScript and XCOM 2. Even on the single main thread that runs the game loop, we can find ways to run tasks concurrently. I personally found it very interesting how early UnrealScript (in UE 2!) had coroutines, a functionality many other mainstream programming languages are only gaining today.

Of course, much of the Unreal Engine 3 remains single-threaded and cannot be parallelized in any way. Future, more efficient engines make more use of the several CPU cores every modern machine has, especially with single-core CPU performance plateauing.