Most XCOM 2 mod developers will in some form be familiar with the History and Templates. And yet, I think it is useful to take a step back and understand the bigger picture around Firaxis' implementation of the Model-View-Controller pattern.

We will roughly outline the motivation behind and the benefits of such an architecture and how the History/GameStateObjects, Templates, Contexts, Actions, and Pawns arise from MVC’s requirements. This will hopefully lead to a more intuitive understanding of their roles.

Finally, we will look at some particular quirks in the XCOM 2 implementation that are useful to know about in order to write robust code.

Motivation

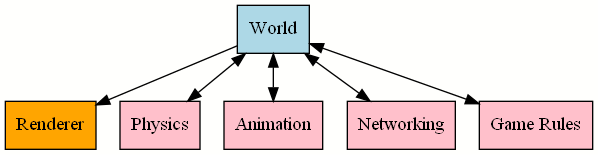

An integral part of a video game is showing things on the screen. The Unreal Engine 3 has some incredible

ways to easily get something to draw on screen: Beyond providing a renderer, there’s a functional world/camera system,

Actors we can attach mesh components to, extending to Pawns providing an animation pipeline and physics.

As soon as we use the engine to draw a soldier on the screen, we already get a significant part of the gameplay-relevant functionality for free. We can use the animation pipeline to implement movement. Multiplayer is already handled by the engine. We give the player a direct presentation and intuitive understanding of the state of the board!

Everything is going great! The prototype advances rapidly, plenty of bugs crop up, plenty of bugs are fixed. And yet, some particular bugs seem to happen more frequently. There are reports of the grappling hook causing its users to fall through the floor under rare circumstances. Multiplayer gameplay performs some actions twice, or not at all. We miss 100% shots.

Worse, we don’t really know how to reproduce and fix these problems – perhaps not even what part of the engine or content is responsible! Do our maps have holes in them so that soldiers fall through? Is the physics engine buggy, or are the animations breaking some rules? Is network replication configured correctly? Do our projectiles live long enough?

Replication is the Unreal Engine 3 solution to multiplayer and networking. It features a client-server architecture, remote procedure calls, synchronization of variables, lossy data compression, reliable/unreliable data and much more.

Nobody in the XCOM 2 community knows how it works and the one remnant (UI functions being marked simulated) continues to be cargo-culted.

This is because replication is entirely irrelevant to XCOM 2. I assume it was quite tricky to get right in XCOM EU/EW.

What these have in common is that systems ostensibly designed for the visual presentation are on the same rank as the actual gameplay:

We have a hard time enforcing invariants and separation of concerns. Nothing could possibly tell the game engine that physics should never move a unit to the adjacent tile when it is idling, or that a unit must successfully land after grappling. Even saving and re-loading a save can’t fix it: Our unit has permanently fallen off the map!

It would be great if there was an authoritative representation of the tactical board, manipulated only by our own gameplay code. The visual presentation would then only read from that representation.

This problem is often encountered in frontend applications and user interface. Of course, buttons can’t fall out of the window, but putting our windowing library and GUI toolkit in charge of our business logic can have similarly bad side effects – outdated display, greyed-out buttons that should be enabled, impossible input, and a lot of shared responsibilities.

It’s not surprising that the solution employed in XCOM 2 originated from user interface development, sometime in the 70’s.

Model-View-Controller

Model-View-Controller (MVC) aims to solve this issue by:

- Defining a clear boundary between the current state (Model) and the visual presentation (View)

- Requiring a clear set of rules through which the model is manipulated (Controller)

- Ensuring that the View has read-only access to the Model and all modifications to the Model are made through the Controller

Don’t attempt to clearly and unambiguously define where exactly the boundary between Model and Controller lies (or what a Controller actually is). Everyone and their grandmother has their own opinion on that topic. For the purpose of this post, we’ll just roll with one particular interpretation – mine.

Flow of information

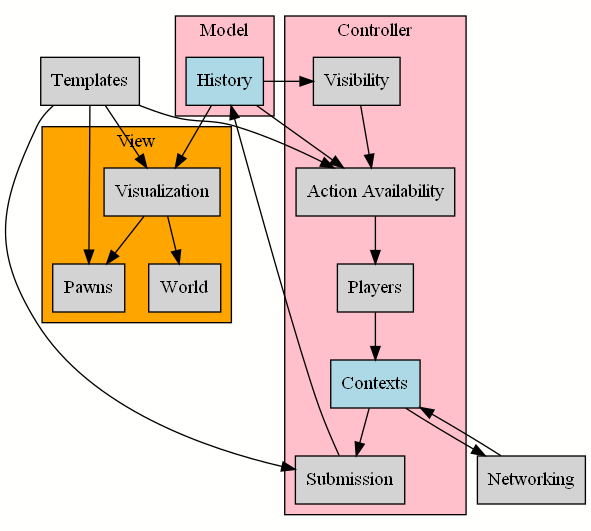

We’ll need XCOM 2 terminology here quite a bit, so here’s a very condensed explanation of the core tactical gameplay systems:

The History stores the current state of the battle. The GameRules manage the player turns and build a list of AvailableActions

for all Players and the currently active Player gets to submit one of these actions in form of a Context.

The GameRules evaluate this Context and submit the resulting changes to the History, allowing reaction abilities to trigger,

giving temporary turns to scampering or reacting units.

The Visualization independently watches for changes to the History and updates world and pawns.

Let’s visualize this in a diagram where arrows denote flow of information:

One thing in particular is worth pointing out right now: No data flows from the View to anywhere else! Evaluation of ability activation does not rely on visualization having occurred. Two AI players, who have inherent access to available actions, could play the game entirely without visualization.

This is a pretty compelling insight into XCOM 2’s MVC: Can the AI play without it? Then it’s View.

Let’s look at some of these parts in more detail!

History Details

Some of this info is also available on the Game States page of the /r/xcom2mods wiki. That particular page contains some useful code samples for directly interacting with the History as it is implemented in XCOM 2.

Objects

We need all sorts of information in our model. Information about units, items, their abilities, applied effects, the state of the mission script, objectives.

It makes sense to use UnrealScript’s inheritance/polymorphism system for this: We create a class XComGameState_BaseObject extends Object;. Everything we

store as part of the model must be a subclass of XComGameState_BaseObject. This rules out quite a bit of nonsensical interactions: We can’t store Actors

in our model (which would be terrible since they’re tied to the world), similarly we can’t store StaticMeshes. Nice and controlled.

In the interest of keeping things succinct, I will abbreviate the XComGameState_ prefix with XCGS_. Instances of XCGS_ classes are called “state objects”.

However, our classes can have arbitrary properties (class variables). Which kinds of these can we save and load? After all, even though we’re

limited to adding state objects to the model, we could simply have a var StaticMesh EvilProperty;. What about var XCGS_BaseObject RefToSelf;? Or other weird data

structures that interface closely with the UnrealScript virtual machine?

The process of saving is called serialization because it transforms a complex structure of objects into a serial byte stream. The opposite procedure, deserialization, follows.

Firaxis made the pragmatic decision to simply not support Object properties when de-/serializing. This avoids cyclicity issues entirely.

Referring to other state objects objects is a legitimate requirement on the other hand – without it, we couldn’t realize that units

actually own items and abilities. The solution is quite simple: We give every state object a numeric ObjectID. State objects keep

this ID throughout the entire campaign and IDs will not be re-used. The model provides a way to get the state object for a

given ID, so we only need to store the ID when referring to other objects. Firaxis wraps this integer in a single-member struct

called StateObjectReference to neuter all the arithmetic functions useful for integers but entirely pointless for IDs.

When implementing your own XCOM 2 state objects, bear in mind that only primitive types as well as structs and arrays are fully supported (except for their Object parts, should they have any). Objects properties are sometimes used for caching purposes precisely because they don’t persist in the save file.

Delegates (references to functions owned by objects) are special and actually participate in serialization.

Avoid var delegate in state objects unless you know what you are doing and you can ensure that the owning

object is a state object or has a persistent name (i.e. the function is a static method).

Frames

This simple model has one problem: Our visualization, generally responsible for visualizing changes, can only view the state at one point in time. Worse, if gameplay advances, visualization may miss certain states and instead look at a future state. It is genuinely useful to be able to look at past and future states!

If a unit was on overwatch in the past state and is now no longer on overwatch, we can show an “Overwatch removed” flyover.

If a movement will result in three other units performing overwatch shots, we can prepare a super cinematic camera movement.

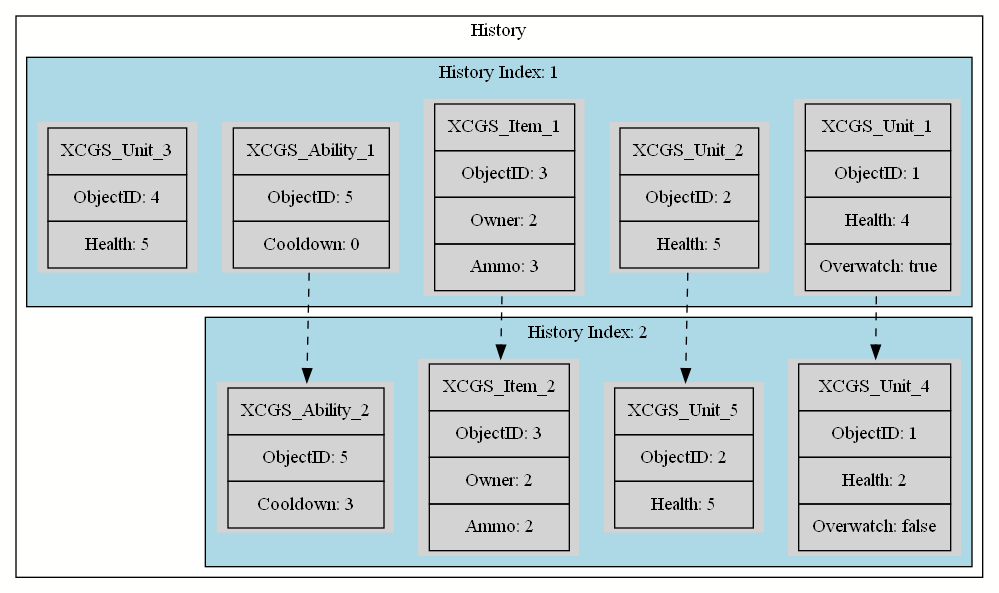

It makes sense to store our model as an append-only list of state changes. Let’s call it the History.

In order to modify the History, we create a new container (XComGameState) and clone the objects before adding them to

this container and modifying them. When it’s done, we submit it to the history.

We call the XComGameState “game state”. Note that game states and state objects (XComGameState_BaseObject, XComGameState_Unit) are different.

To make things more confusing, “state” can refer to game states as well as state objects, for example “unit states”.

To disambiguate, game states are sometimes referred to as “history frames”.

As an optimization, we only need to clone the objects we are interested in modifying:

In this example, Unit 2 shot Unit 1 with Item 3 using a free Ability 5. Unit 2 did not change at all, but is still part of the updated state because it generally makes sense to have the shooter in the game state. Unit 1 lost health and the Overwatch status, Item 3 used ammo. Unit 4 did not participate in the action at all.

Even though the object names change, the IDs stay the same. The ObjectID can be used to uniquely identify and track all state objects!

Hold on to and pass around StateObjectReferences, not XCGS_ objects. The more state objects you pass around, the higher the risk of using outdated information.

On the other hand, simply requesting state objects from the history may result in you looking into the future. You can query game states for state objects and ask the History for the state objects at arbitrary history indices. This is especially important for visualization, which may end up spoiling results if it doesn’t look at state objects from the exact history index as the visualized game state.

This allows us to answer all kinds of queries and enables as a bonus a History replay feature: We can load a completed tactical save in replay mode and step through the history, never submitting anything on our own.

In Context Of

Now that we have a rough understanding of the History, it’s time to consider the role of the Contexts

(classes with an XComGameStateContext_ prefix, here abbreviated as XCGSContext_, sometimes also XCGSC_). In our original diagram,

players and networking submit contexts in order to initiate changes in the history. Why go through this extra hoop?

It turns out that players can’t actually be trusted to play by the rules. Permitting the AI as well as human players to build their own game states is dangerous: Both AI and UI may operate on outdated information and essentially “cheat”. It is far safer to present players with a list of available actions and let them choose one action. The game rules can validate this action easily – after all, the game rules handed out the action in the first place.1 The context can then build the game state and the game rules add it to the History.

The XCGSContext_Ability contains little information, but enough to deterministically build the game state.

In our example, it would contain something akin to “Unit 2 uses Ability 5 with Item 3 against Unit 1”. Contexts are stored together with their corresponding game state.

This has some great advantages:

- Multiplayer can be realized by sending the contexts only and letting both sides evaluate the context and build the game state independently

- Daily mission leaderboards can be validated by validating the contexts and checking if they create the same game states

- The tactical tutorial (a special history replay) can be realized by simply checking if the to-be-submitted context matches the stored context (rejecting it otherwise) and just not submitting anything, instead advancing the replay

All tactical user input must submit a context to achieve changes. It’s perfectly fine to submit game states directly in response, for example from event listeners, as long as the entire event chain can deterministically be triggered from the original context.

In other words, game states contain the answer to “what changed?”, contexts the answer to “why did it change?”

Inputs and Outputs

Unfortunately, one piece is still missing: We don’t know about some intermediate results that lead to the changes. In our example, did the shot graze and deal 2 damage, or did it miss but deal 2 damage due to the stock weapon upgrade?

Fortunately, since we store the context in the History, we can simply store that information in the context itself.

The XCGSContext_Ability thus has variables part of the input context (who used what against whom?) and part of the output context

(what’s the hit result and damage values? which effects applied successfully?)2

Interruptions

Contexts play another important role because they can produce more than one game state (the context will be cloned for every game state).

For example, every regular ability activation first submits a “fake” activation (eInterruptionStatus_Interrupt) that triggers relevant events,

but doesn’t actually apply any effects. This gives reaction fire abilities a chance to react before the ability performs its effects

(consider Overwatch + Covering Fire).

If nothing happened in response, this fake game state is removed from the history and the ability is properly activated (eInterruptionStatus_None).

Otherwise, the original game state and all response game states are kept, a copy of the original context is re-validated (the unit may have died from reaction fire),

and this copy is properly submitted (eInterruptionStatus_Resume).3

Further, movement abilities trigger an interruption game state for every single step. Only the steps actually causing a reaction and the final step are kept. If no response actions are performed along the path, the movement is a single jump from source to destination.

If you have an event listener for successful ability activations, you may want to filter interruption steps with

if (GameState.GetContext().InterruptionStatus == eInterruptionStatus_Interrupt) return ELR_NoInterrupt;, lest your code runs twice for every ability activation.

With all this in mind, it’s perhaps best to review the architecture diagram and see if it makes more sense.

Templated

Templates sort of transcend the entire system. They contain view data, game rules input, and instructions for game rules.

Dissecting the X2AbilityTemplate, we have:

- View

- Ability icons

- Targeting methods (allowing the user to select an action)

BuildVisualizationFn(prepares the visualization for activated ability)

- Game rules input

- Conditions

- Costs

- Target styles (building the list of actions)

- Game rules instructions

- Effects

- Costs

BuildNewGameStateFn(builds the game state for activated ability)

This is, of course, not a violation of MVC. We factored all of these aspects into the original architecture diagram. No data flows from View to anywhere else.

Archived

Our approach to the History has the problem of unlimited growth. With every mission, our save file contains more and more objects, and more and more versions of the same object. This would spiral out of control quickly. Firaxis employs a number of mitigations.

TacticalTransient objects are never retained after the end of a tactical mission. This includes ability states, effect states, and players.

You can make objects TacticalTransient by setting the class variable bTacticalTransient in defaultproperties:

defaultproperties

{

bTacticalTransient=true

}

Items and Units are not TacticalTransient, so even dead enemies and their items from tactical missions are retained. Additionally, we still store more and more history frames and contexts even though we don’t need to look back into what happened on turn 3 of Gatecrasher.

StartStates are game states that act as a barrier. When we go from strategy to tactical, we create a start state and copy everything relevant into that start state. This includes units in the squad and excludes units not in the squad. When we iterate over all units in the History from now on, we only get the units actually on the battlefield.

Start states are the only game states that are allowed to be modified after being submitted as long as they’re the latest game state in the history. They are usually combined with a History lock that prevents other game states from being submitted.

The strategy->tactical transition is a relatively complex series of loading maps, instantiating state objects for map actors, spawning units, and setting up the mission script, all while the start state is on top of the History. At some point the History is unlocked and everything proceeds as normal.

At the same time, submitting a start state causes all previous game states to be squashed into a single game state with an “archive” context. At the end of the battle, this archive state is retrieved, its objects are copied into the new strategy start state, and the objects are updated with their tactical versions in case they participated in the tactical session.

The tactical History is missing objects. If you use OnLoadedSavedGame to make modifications with the installation of your mod, your changes may find some

strategy objects missing. Prefer a combination of OnLoadedSavedGameToStrategy and OnPostMission.

If you write code that relies on certain objects being brought along in a strategy->tactical transition, you can add them in OnPreMission.

Ideally this would mean that at some point, all enemy units and their weapons would be left behind. Unfortunately, there are multi-part missions like the Shen’s Last Gift tower mission. This tactical->tactical transfer would mean strategy objects would be left behind, so we can’t leave objects behind and the archive state continues to accumulate some garbage.

There is an attempt to fix it in the Highlander. Everybody is scared to approve it because it may delete important units from mods that re-use base-game templates.

Violations

There are a number of ways you can violate MVC:

- Directly submit game states from user input in tactical

- Modify state objects part of already submitted game states

- Submit contexts or game states from visualization

- Make changes dependent on the current state of the visualization

- Cause observable side effects from code building a game state

- Attempt to build a game state while there is a game state currently being built

Sometimes it’s not obvious whether a game state is “in flight”. Event listeners registered with ELD_Immediate for events triggered

in game state code can usually rely on NewGameState being in flight and mutable, but event listeners registered with ELD_OnStateSubmitted

cannot. The Events/Deferral section of the /r/xcom2mods wiki

elaborates on this point further.

Moreover, a game state might sometimes be in flight due to multi-threading/latent submissions in WotC. This deserves a separate blog post,

just don’t submit a context while `XCOMGAME.GameRuleset.IsDoingLatentSubmission() returns true for now.

For the rest of the blog post, we’ll look at some particular violations that happen in base-game code.

Unconscious Units

Units knocked out will have a knockback effect applied to them that may move them to a different tile. Physics rarely cooperate, so once the ragdoll settles, it submits a game state that corrects the unit’s position.4 This ensures the unit is where players would expect it to be, but can cause race conditions with AI code.

I think this violation is not justified, especially in face of the practical issues it causes with AI.

Hit Rolls

A perhaps surprising fact is that rolling for an ability hit happens entirely before a game state is built, despite the RNG seed definitely being part of the Model. Abilities actually support not submitting a game state upon failing to roll a hit. No abilities make use of this, but it seems like it was intended to work for the concealment system, where enemies would have a chance to notice player units.

This is a small violation as long as it only happens in reaction abilities / responses to events.

More seriously, some effects directly write to state objects in the history as part of determining ability hit results.

Consider this simplified function from X2Effect_Parry:

function bool ChangeHitResultForTarget(XCGS_Unit TargetUnit, out EAbilityHitResult NewHitResult)

{

if (TargetUnit.Parry > 0 && TargetUnit.IsAbleToAct())

{

NewHitResult = eHit_Parry;

TargetUnit.Parry -= 1;

return true;

}

return false;

}

This is about as serious in that it only happens in response abilities, but it does write directly to the History. Bad idea.

There are two kinds of random functions: The built-in Rand() function and the Firaxis `SYNC_RAND() macro.

Use Rand() for visualization and `SYNC_RAND() for game state code – the former does not affect the saved RNG seed, the latter does.

Achievements and Mission Completion

Steam/platform achievements are triggered when the game state is built. This essentially spoils results because the achievement pops up as soon as the player hits the “confirm” button. This could easily be fixed by making achievement unlocks part of the visualization.

Every context has a PostBuildVisualizationFn delegate array that can be added to from game state code in order to add additional visualization

even if you don’t control the variables in the context.

Similarly, upon confirming the action that will complete the mission, all UI is hidden.

These are not MVC violations because no data flows from view, but more visualization bugs.

Map

At a glance, the map seems like a giant MVC violation. Actors are responsible for building the tile grid, pathing and visibility. Further, even though a lot of map actors are destructible, almost none of them have corresponding state objects.

This is handled by native code, but upon further inspection, the world data seems to be able to speculatively apply environmental damage and update visibility and pathing internally without visualization having occurred.

Moreover, even though destructible map actors generally have no state objects, saving and loading retains environment damage. This is because the events that lead to map destruction are part of the history and simply re-played upon loading a saved game.5

If we recall our AI insight (“does the AI need this?"), then it’s resoundingly clear that the map and its meshes are part of the state too. It’s iffy and okay to feel a bit uneasy about, but it works OK-ish.

Sometimes map actors like to self-destruct right after confirming an action, but this could easily be just a visualization bug, not an MVC violation.

Cursor targeting

Pixel hunting is the XCOM player’s favorite obsession. Unsurprisingly, grenades and heavy weapons allow freely targeting the ability on the tactical map, so the game rules don’t actually provide a list of all available actions and leave it to the players, which mostly results in the AI hitting seemingly (and sometimes actually) impossible shots – players create the target for cursor-targeted abilities on the fly and there’s no validation.

On top of that, some targeting methods actually use info from the unit pawn to build the heavy weapon path, particularly around visibility checking and ray tracing.6

There’s no good solution for the first problem. Even tile-snapping would result in a huge possible target list. The second problem is a plain old MVC violation that should have been addressed by using the unit state tile location and not the actor location.

Strategy

This article was focused on tactical. The strategy gameplay is a lot less principled about this, knows no concept of available actions and often submits

ChangeContainers (a dummy context where the game-state is pre-built already) directly. Narrative moments randomly interfere and cause race conditions

with UI screens that have pending game states (like customization). Strategy keeps the History for state management, but doesn’t concern itself with MVC at all.

Closing Words

I hope this article was insightful and helped you understand XCOM 2’s tactical architecture. Moreover, I hope you will keep the presented concepts in mind and use them to confidently write and review code that interacts with the History, Contexts, and tactical MVC.

I would like to thank Xymanek for reviewing a draft of this blog post and providing valuable feedback.

See

X2TacticalGameRuleset:GetGameRulesCache_Unit↩︎See

XComGameStateContext_Ability:InputContext/OutputContextand corresponding definitions inX2TacticalGameRulesetDataStructures↩︎See

X2GameRuleset:SubmitGameStateContext_Internal↩︎See

XComUnitPawn:SyncCorpse↩︎See

XComGameState_EnvironmentDamage↩︎See

X2TargetingMethod_RocketLauncher:Update, particularlyFiringUnit.Location↩︎